Finally, continuing from part 2, last but certainly not least, we need to talk about color.

Color accuracy in ANSI is something that was occasionally discussed around the scene even in the DOS days, but those issues mostly centered around the particulars of an individual’s monitor’s brightness and contrast settings (or perhaps how rich of a layer of dust had amassed on its surface over the years.) That’s to say, the 4-bit (16 color) VGA palette was pretty much a known quantity. In fact, for backwards compatibility reasons both VGA and earlier EGA’s 4-bit palettes were based on the original Color Graphics Adapter (CGA) modified RGBI palette.

Enter “New Technology“. It took a while for most people in the BBS scene to notice or care since most of us kept running the much more MS-DOS adjacent Windows 9x series of operating systems, but change was in the air. I recall making the switch to using Windows 2000 Professional at work. The first time I did some playing around with an old DOS program, or perhaps it was mTelnet, I was jarred by how utterly jacked up the colors in Windows NT’s new CMD.EXE console looked. Soon after, my friend and sometimes collaborator Grymmjack put out a little release that included a Windows registry file to make the necessary changes to correct them. This file became absolutely mandatory to me and many others as droves of home users finally migrated to the NT series of operating systems with the release of Windows XP in 2001.

So what’s going on with the colors in CMD.EXE? Well, if each of the RGB color values in the 4-bit VGA palette is represented by a value from 0-255, the dark colors are 2/3s the intensity of the bright colors. In other words, 170. Likewise, when an even darker color is desired for mixing colors, 85 is used. Dwelling on this seemingly odd approach a little, I believe the intent may have been that since 0 is considered a color (black) and 255 is most definitely a color (white) only two additional values were needed, with 85 and 170 quartering the scope. Makes sense!

CMD.EXE’s colors, however, seem to be based on the standard 16 color RGB palette. The scope is quartered with the assumption that black is the absence of color. That means we go from 1, to 64, to 128, to 192, to 256 (despite actually being zero-based.) More importantly for our purposes, dark colors use a value of 128 which is 1/2 intensity instead of 2/3s. Whoa! Much more damning, this palette largely does away with the finer mixing of colors with the 1/4 value, meaning the infamous color 6, brown, is now “dark yellow” or “olive” and our bright blue no longer has its beautiful icy hue. Another telltale sign that our palette has been tampered with is that every ANSI artist’s favorite color 8, dark grey, is substantially lighter in this palette. The 4-bit color table in this article demonstrates this well with its first two columns.

Having figured all of that out, one thing I haven’t been able to find any information on is why this was done. Was it the “New Technology” team at Microsoft wanting to cast out the CGA RGBI palette like the dusty old relic that it is? Was it perhaps an intentional shift to a standard RGB palette for some particular technical reason? Maybe it was all a mistaken assumption made by a lone Microsoft developer that has continued to be overlooked all these years? I don’t know. One thing I do know is that it sucks for us ANSI enthusiasts.

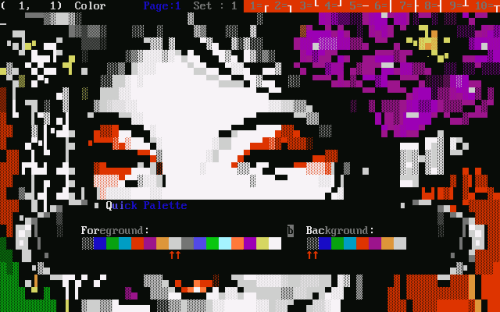

Now, with Windows 10 Microsoft has thoroughly tossed out all of the old standards, coming up with a new color scheme called “Campbell” seemingly based on, well, absolutely nothing. This is, instead, apparently an intentional effort to make the colors have higher contrast on modern LCD monitors. Curiously, the palette itself seems to have much less contrast when viewed as a whole. Whatever. For ANSI, these new colors are a total disaster – we have a weirdly orange reds, an almost tan brown, barely distinguishable dark and bright purples. I just… can’t.

So, how do we fix this? Well, if you’re using any version of Windows prior to Windows 10 version 1709 AKA “Fall Creators Update” then the very same registry hack that I mentioned we used to use almost 20 years ago will still work today. Here is a quick bonus archive with my take on all three of the described color schemes in separate registry files for those wanting to experiment. Unfortunately with the newer color scheme changes Microsoft seems to have also changed how CMD.EXE stores its color settings, though you could always try to compile the new “Colortool” and build your own equivalents using the classic RGBI color values. More likely, you’ll just want to go to the properties of your console window, click the “Color” tab, click each individual color, and customize the RGB values there to match those same RGBI colors. While you’re in there, you might as well change your cursor size to “Small” under the “Options” tab and don’t forget to fix your font too.

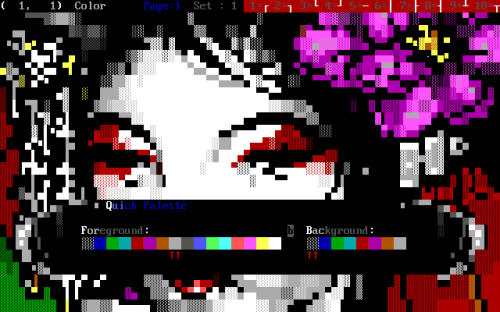

Here’s my terrible command prompt in Windows 10 using the old CMD.EXE colors (since I upgraded to version 1709 the new color scheme wasn’t forced upon me.) Did I mention that Windows 10’s CMD.EXE now parses ANSI escape codes natively? I just used the “type” command to display this dope Grymmjack ANSI!

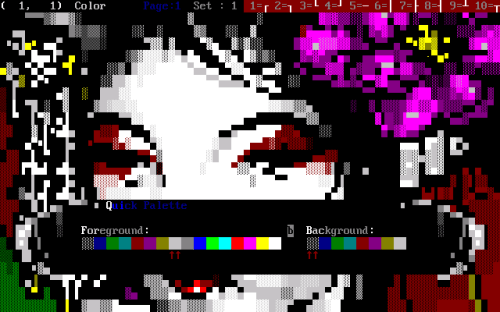

Here it is again after fixing the RGB values of the 16 colors, setting them back to the proper RGBI palette. Notice how the dark blue and purple are a little brighter? How bright blue is, well, a totally different color? How the shading seems to be blended a little better, and how the cyan highlights on the font look more appropriate? Most importantly, dark grey has been restored to glory?

Ahhh, much better!

—

1. fil-koku.ans by Filth from Blocktronics: Awaken (2003)

2. gj-drk.ans by Grymmjack from Used #4 (2000)