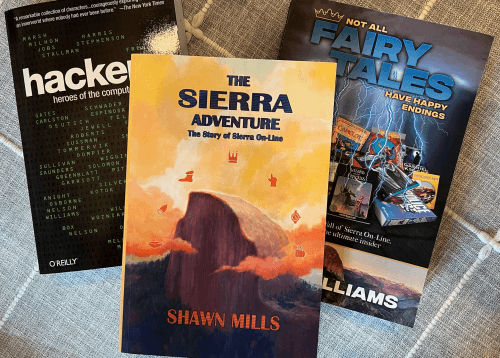

I read (and listen to) a lot of books related to computer history, the computer underground, and computer and video games. You know, the type of things I should probably talk a bit more about here! Actually, I’m mostly done writing a post where I quickly review a number of my more recent reads. First though, having just finished one such book, I figured I’d make a post devoted strictly to books about the history of one of the most fondly remembered classic personal computer game developers, Sierra On-line. Fondly enough for me to talk about three different books, at least!

As an aside, I’ve yet to talk much about gaming on this blog. That is definitely something I hope to thoroughly rectify as collecting and playing classic computer games is an important aspect of my interest in retro computing. Sierra On-line is one particularly big component of that, as during their heyday they were without question one of my favorite developers (and when you throw in another of my all time favorites, Dynamix, one of my favorite publishers too.) Sure, LucasArts is widely agreed upon to be the victor when it comes to the fanboy favorite argument of which of the two companies made the best adventure games, but in the 90s Sierra held much more territory in the diskette and CD-ROM boxes of my personal game collection; the Space Quest series in particular being an all time favorite.

Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution by Steven Leary is surely one of my favorite non-fiction books; when I eventually stumbled upon it I honestly couldn’t believe I hadn’t read it much, much earlier in life. I’ll review it more generally in that aforementioned book review post, but of relevance here is the last third or so of the book which focuses on the shift of personal computer software development, while still somewhat rooted in enthusiast hacker culture, to a more commercial direction in the early 1980s. In particular, it mostly focuses on Ken Williams and Sierra On-line. Keeping in mind that this book was first published in 1984, this was a very contemporary look at what was then a fairly young version of Sierra, having only just released the original King’s Quest.

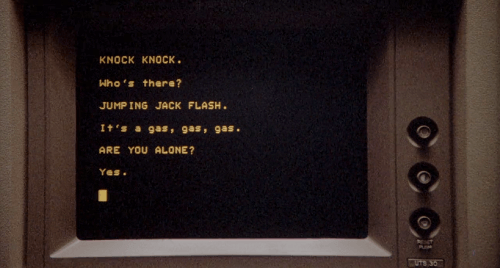

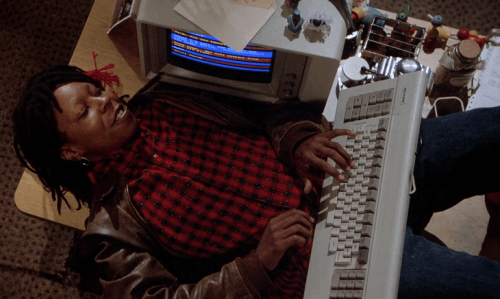

Of course the story of the founding of On-line Systems and the development of Mystery House is covered, but then Hackers moves into chapters devoted to Sierra’s close bonds with their peers, such as Brøderbund and Sirius Software, its “summer camp” like culture, and its gradual shift away from that and “hacker” ethics in general, along with all kinds of now legendary stories including the deal with IBM to develop for the PCjr, Richard Garriott joining Sierra, the noncompete lawsuit against Atari, and a whole lot more. The style of these later chapters is a bit different than those earlier in the book, feeling more like embedded journalism pieces than chapters in a book about computer history. Crucially, Hackers really provides a different take on who Ken Williams was and how he ran Sierra at the time than what I was familiar with. This is extremely fascinating stuff and absolutely essential for providing some eye opening accounts of those typically skimmed-over early years of the company.

I’m sure there had to be some, but I don’t know of anything else significant outside of blurbs posted in Sierra’s own manuals, guides, and magazine until 2018, when The Sierra Adventure was published. I was stoked. At long last someone put together a book about the history of the venerable Sierra On-line! The author, Shawn Mills, is a writer for Adventure Gamers and one of the founders of Infamous Quests, a throwback adventure game developer best known for Quest for Infamy and a couple of notable Sierra remakes. Respectable bonafides!

The Sierra Adventure isn’t quite the exhaustive chronicle of the history of the Sierra On-line and every last one of its products that many might be looking for in such a book. Instead, it attempts to approach the subject almost entirely from interviews with former employees. Quite a lot of notable people contributed the quotes that make up the bulk of the book’s content, though Ken and Roberta Williams themselves, still keeping a distance from all things Sierra at this point, are rarely quoted. Even still, there is enough here and I think the author put it together with enough love to make it a worthwhile read. I have to say, I was a bit annoyed with how the book starts, devoting its first chapter to flashing just a bit forward to talk about Sierra’s first couple brushes with death and how the company survived them before going back and starting at the beginning with On-line Systems and Mystery House in the next one. This kind of literary device often works quite well, but here it just came across like some kind of a bizarre editing snafu. A relatively minor gripe, I admit.

In 2020, founder and former CEO, Ken Williams himself, wrote and published Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings. Part autobiography, part industry insider insight, Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings is the story of Sierra On-line from the unique perspectives of Ken, and to a lesser extent, Roberta. While I did sometimes find the writing in need of a bit more editing (for example, Ken often repeats himself, especially from chapter to chapter) I quickly started to get in tune with Ken’s “voice” and ended up really enjoying his take. By the way, I originally listened to the audiobook version, and when I later got a printed book I was surprised to find it full of interesting full color pictures. Very much an upgrade!

Without a ton of detail, the book sometimes feels like just a bunch of strung together anecdotes, though it was all strung together reasonably well despite its numerous interludes. It certainly succeeded in satisfying my biggest hope for the book by filling in a lot of gaps about Ken and Roberta and the unique company culture that produced the games I loved so much. I was perhaps most intrigued by the conflict between Ken’s cold and detached approach to business: only wanting to work with “A players” and chasing monetary success, at times to the detriment of the company, with his more personable and generous side: hiring random locals to grow into very specialized positions and running the company like a big, fun family, and how that stuff all changed as he eventually ceded more of Sierra’s management and control to others as the company grew. I don’t know that Ken sees this as a “conflict” himself but, especially given Sierra’s eventual decline, it stood out to me. Speaking of which, this book gave me far more insight into the death of Sierra than anything else I’d read, with Ken providing a version of events that no one else has ever, or could ever, fully present around the CUC takeover and subsequent loss of control. It really is, as the title suggests, a bit of a cautionary tale.

Of course, Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings is all from Ken’s point of view but, despite the obvious inherent bias there, his accounts do come across as sincere to me. Regardless, I’d highly recommend reading the sometimes overlapping accounts in all three of these books for a more well-rounded perspective. I’d also recommend reading them in the order I covered here; Ken even references his chapters of Hackers in Not All Fairy Tales. When taken together, we finally have as close to a complete picture of the company as we’re likely to ever have.

There you have it! Needless to say, these are far from in-depth reviews and I’d recommend Evan Dickens’s reviews and comparison between The Sierra Adventure and Not All Fairy Tales over at Adventure Gamers if you want to dive a little deeper than I did here.